Kiarostami forest at the V&A (LONDON) http://www.artdaily.com/section/news/index.asp?int_sec=2&int_new=12901 Iranian Director Abbas Kiarostami and British Ken Loach have teamed

to make a film called "Tickets" a sort of sketch Comedy presented

at the 2005 Berlin Film Festival: See Full cast and article

The first problem which arises is how the three ?auteurs? managed to work together, how they succeeded to do separate films within the same structure. Both filmmakers present at the discussion ? Loach and Kiarostami ? argued that everybody made his own movie. ?There is no other way of working, you have to follow the internal logic of your own subject?, Loach said. Kiarostami added that real communication between them begun only when linking the parts together. Not only three directors, but three different cultures and languages were brought together for the movie. For Kiarostami, the shooting proved that ?language is not the most important thing because you can communicate with your physionomy, with your faces and with your eyes.? So cultural differences can be overcome. Asked about the element common to all three directors, Loach said:

?What we share is the attempt to reduce things to the simplest way of

explaining something. Reducing and clarifying is not what you see in

most films which tend to exaggerate, to make things dramatic. That kind

of simplicity, clarity and economy is something we would like to share.?

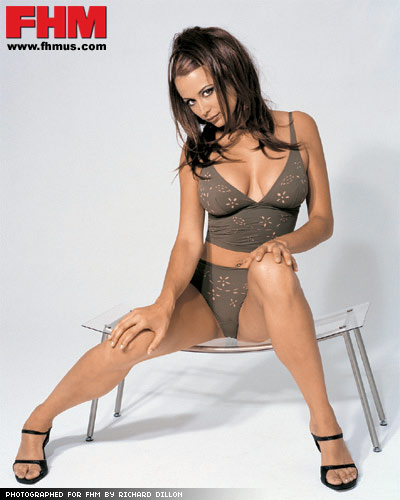

We can't ignore that this movie ? especially Loach's segment ? has political connotations, so this question appeared during the discussion too. The English director talked about the gesture of the Celtic fans who shared what they had with the Albanian refugees. He compared this to the reaction of the world to the tsunami appeal. He argued that everybody put his hand in the pocket, because all of this was encouraged by the media and politicians, but nobody does the same thing with the people killed in Iraq. Three styles are put together in the same small world of a train and, despite the differences, something seems to unite the visions. Sexy Actress Catherine Bell who is half Iranian-half British and popular

Star in US series 'JAG' in which she happens to speak in Farsi at times

( A breakthrough I believe in US series) Omid Djalili (R) to star in the new movie Mogdigliani as Pablo Picasso alongside Andy Garcia http://us.imdb.com/title/tt0367188/

Turtles Can Fly: by: Bahman Ghobadi 'I come from a land of untold stories'

Bahman Ghobadi has made the first film to come out of post-war Iraq – about children who survive by collecting mines, sometimes with their teeth. He talks to SF Said Turtles Can Fly happens to be the first film to come out of post-war Iraq – but even if it wasn't, it would still be extraordinary. Forget the explosive context, the searing topicality: it's about the human spirit – our power to survive, and the limits to that power. It's made by Bahman Ghobadi, director of A Time for Drunken Horses. This was one of the most emotionally compelling films of recent years, telling the true story of children who work as human mules, smuggling contraband over the Iran-Iraq border. Like that film, Turtles Can Fly is about children in conditions of unimaginable danger. This time, they're Iraqi Kurds, living through the period around the Iraq war and the fall of Saddam Hussein. The adults in their world are either dead or unreliable. To survive, they clear up unexploded landmines and sell them on the black market. Some lose limbs doing it; some don't survive. Yet they show such deep resources of courage, humour and tenacity that you cannot but be touched. "I come from a land full of untold stories," says Ghobadi, 36. "It's a land of exceptional events. There is always something happening - so many stories, sometimes I can hardly breathe." The film centres on three children: a young entrepreneur nicknamed Satellite, a girl he falls in love with, and her brother. The brother and sister are orphaned refugees from Halabjah (the Kurdish town Saddam Hussein's forces attacked with chemical weapons in 1988). The boy has lost both his arms sweeping minefields, and now uses his teeth to pick them up instead. Ghobadi shows us the consequences of conflict - not on the grand geopolitical stage, but at the level of ordinary people's lives. He shows us images we might prefer not to see, but which are commonplace in today's Iraq. Indeed, the film started out as a documentary. "Two weeks after Saddam's fall," he says, "I went to Iraq with a small camera, just for my own use. And I was recording all these kids with no arms or legs, all the mines, the arms bazaar. When I came back to Teheran, I wanted to write a story that would take me to those places." Turtles Can Fly is that story. It's fiction, but the children who act in it are portraying their own lives. The boy with no arms really has swept minefields for a living. "They have experienced it," says Ghobadi. "You can't believe it, but there are more than 30,000 kids like him in Iraq. Often they cannot cope. He was one of the few who somehow had the fighting instinct in him." "This is Kurdish life," says the director. "This is how the people are. They express their love; they laugh a lot. So when I wanted to reflect what was going on in Iraq, I had to bring a sense of humour into it, because this is how the Kurds survive their hardships." Ghobadi's films reflect his own experiences. An Iranian Kurd, he grew up in a small town near the Iraqi border. Many members of his family perished during the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s. "As a child, I thought of it as a nightmare," he says, "but it was reality. And now it's coming out in my films, because other children are living it too. It's like taking something out of your chest, and putting it on film." Despite a history of demands for independence, Kurds have never had their own state. Kurdistan encompasses parts of Iran, Iraq, Turkey and Syria. Yet Kurds conceive of it as one country, and to Ghobadi, Turtles Can Fly is set in that country. "I'm a Kurd, that's where I'm from," Ghobadi says. "Somebody drew a line on a map, but most of my family and friends live in Iraqi Kurdistan. When I go there, I don't feel I'm in a foreign land. I feel at home." He became a filmmaker to give voice to such feelings. He was lucky to come of age at a time when Iranian cinema could nurture a wide range of talents. He assisted the likes of Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf, and acted in Samira Makhmalbaf's Blackboards. Yet his films are not typical of Iranian cinema. They have a naked emotional rawness that touches nerves without feeling exploitative or sentimental. They also have very clear, direct narratives. Ghobadi once told an interviewer that he didn't want "a single frame" of his work to be like a Kiarostami film. He's been successful on his own terms, and that fact is encouraging others, especially the young people who work with him. "I get attached to them," he says. "The boy in A Time for Drunken Horses became my assistant on my last film. In two months, he's going to direct his first feature. The boy who plays Satellite will be his assistant. Probably he'll make films too, later on. But sometimes I doubt. I'm helping a few kids - but there are 30 million people who need help. What can a filmmaker do?"

Ridley Scott's new Crusades film 'panders to Osama

bin Laden' Sir Ridley Scott, the Oscar-nominated director, was savaged by senior British academics last night over his forthcoming film which they say "distorts" the history of the Crusades to portray Arabs in a favourable light. The £75 million film, which stars Orlando Bloom, Jeremy Irons and Liam Neeson, is described by the makers as being "historically accurate" and designed to be "a fascinating history lesson". The film, which began shooting last week in Spain, is set in the time of King Baldwin IV (1161-1185), leading up to the Battle of Hattin in 1187 when Saladin conquered Jerusalem for the Muslims. The script depicts Baldwin's brother-in-law, Guy de Lusignan, who succeeds him as King of Jerusalem, as "the arch-villain". A further group, "the Brotherhood of Muslims, Jews and Christians", is introduced, promoting an image of cross-faith kinship. "They were working together," the film's spokesman said. "It was a strong bond until the Knights Templar cause friction between them." The Knights Templar, the warrior monks, are portrayed as "the baddies" while Saladin, the Muslim leader, is a "a hero of the piece", Sir Ridley's spokesman said. "At the end of our picture, our heroes defend the Muslims, which was historically correct." Prof Riley-Smith, who is Dixie Professor of Ecclesiastical History at Cambridge University, said the plot was "complete and utter nonsense". He said that it relied on the romanticised view of the Crusades propagated by Sir Walter Scott in his book The Talisman, published in 1825 and now discredited by academics. "It sounds absolute balls. It's rubbish. It's not historically accurate at all. They refer to The Talisman, which depicts the Muslims as sophisticated and civilised, and the Crusaders are all brutes and barbarians. It has nothing to do with reality." Prof Riley-Smith added: "Guy of Lusignan lost the Battle of Hattin against Saladin, yes, but he wasn't any badder or better than anyone else. There was never a confraternity of Muslims, Jews and Christians. That is utter nonsense." Dr Jonathan Philips, a lecturer in history at London University and author of The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople, agreed that the film relied on an outdated portrayal of the Crusades and could not be described as "a history lesson". He said: "The Templars as 'baddies' is only sustainable from the Muslim perspective, and 'baddies' is the wrong way to show it anyway. They are the biggest threat to the Muslims and many end up being killed because their sworn vocation is to defend the Holy Land." Dr Philips said that by venerating Saladin, who was largely ignored by Arab history until he was reinvented by romantic historians in the 19th century, Sir Ridley was following both Saddam Hussein and Hafez Assad, the former Syrian dictator. Both leaders commissioned huge portraits and statues of Saladin, who was actually a Kurd, to bolster Arab Muslim pride. Prof Riley-Smith added that Sir Ridley's efforts were misguided and pandered to Islamic fundamentalism. "It's Osama bin Laden's version of history. It will fuel the Islamic fundamentalists." Amin Maalouf, the French historian and author of The Crusades Through Arab Eyes, said: "It does not do any good to distort history, even if you believe you are distorting it in a good way. Cruelty was not on one side but on all." Sir Ridley's spokesman said that the film portrays the Arabs in a positive light. "It's trying to be fair and we hope that the Muslim world sees the rectification of history." The production team is using Loarre Castle in northern Spain and have built a replica of Jerusalem in Ouarzazate, in the Moroccan desert. Sir Ridley, 65, who was knighted in July last year, grew up in South Shields and rose to fame as director of Alien, starring Sigourney Weaver. He followed with classics such as Blade Runner, Thelma and Louise, which won him an Oscar nomination in 1992, and in 2002 Black Hawk Down, told the story of the US military's disastrous raid on Mogadishu. In 2001 his film Gladiator won five Oscars, but Sir Ridley lost out to Steven Soderbergh for Best Director. _______________________________________________________________________________________ FRANCE's HOTTEST STAR: JAMEL DEBOUZE France's Hottest and most popular Star is no more the

gallic Gerard Depardieu, his status is being surpassed by a young prodigy

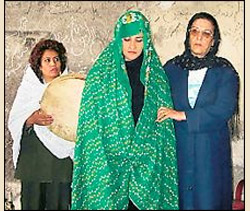

a stand up comic called Jamel Debouze. _______________________________________________________________________________________ Interesting Article on Theater in Afghanistan (Irandokht) KABUL, AFGHANISTAN – Barely three years ago, at a time when women

in Afghanistan were not permitted even to leave their homes, the idea

of a woman performing on stage - and in mixed company! - seemed inconceivable.

Any woman who did so risked life and limb.

Her words hint that opposition to women on stage - and perhaps to live theater in general - is not entirely a thing of the past. Indeed, the festival devotes a day to "women's theater" which challenges Islamic fundamentalists who would block women's ascent to the stage - not to mention school, jobs, and other aspects of civic life. But the country's first theater festival ever, and the participation of about two dozen newly formed dramatic companies from around the country, speaks to how quickly this Muslim country is evolving and to the role the arts are playing in its transformation. To those who support this flowering of Afghan theater, drama is an effective way to spread the message of a modern, democratic Afghanistan. "People may not listen to the mullah, but they will pick up good things when they come to the theater," says Majid Ghiasi, director of the government-financed Kabul Theatre Company. "The message conveyed through drama or comedy is more easily absorbed." The Kabul Theatre Company has toured several provinces in the past year, presenting short plays on themes such as women's education and the importance of democracy. Audiences have greeted the troupe with enthusiasm, even in villages. Only once did trouble arise, when fundamentalist university students stormed a performance in Jalalabad. Hostile reviews Many Afghans, though, continue to regard theater as inappropriate for women and some see it as in conflict with Islam. Female performers at the 45-play festival in Kabul will wear a hijab, the traditional head covering prescribed by Islam. But the audiences will be mixed and women's voices well represented. Naseeba's half-hour play, to be performed by the Mediothek Girls' Theatre from the northern city of Kunduz, is just part of her repertoire. The teenager has written, directed, or acted in 15 short plays for the German-sponsored girls' theater company in the three years since a US-led coalition force swept the Taliban from power. Before that, she could not even attend school in Afghanistan and received her education as a refugee in Iran. "Theater is an easy medium," says Nobert Spitz of Germany's Goethe Institute, which supports the Afghan theater revival and is helping to organize the festival. "It travels by bus, it doesn't need electricity, it can go to the remotest region, and the audience needn't be literate." Afghanistan has a long tradition of rustic theater - storytellers enacting religious myths and legends, or vaudeville-type entertainers performing at weddings. But modern Afghan theater was born less than a century ago, at the initiative of King Amanullah. The first production, about 1920, was of a patriotic play, "Mother of the Nation," performed in the royal garden retreat of Paghman, near Kabul. With Afghans' love for music and melodrama, theater flourished in the cities. In the early 1960s, a state-of-the-art, German-designed National Theatre opened in Kabul, with a revolving stage, an orchestra pit, and seating for 700. Theater's underground resistance The art form did not fade with the rise of the Communists in the 1970s: During the Soviet occupation, Kabul's police and firemen even had their own theater groups. But the mujahedin militias who drove out the Communists in 1991 also dimmed the lights of theater. The bombed-out hulk of Kabul's National Theatre stands as stark testimony to the assault on Afghan culture during the mujahideen civil war, and by the short, brutal reign of the Taliban. "Theater was suppressed all over the country under the Taliban, but curiously, not in Kabul University," says Mohammed Azeem Hussainzada, head of the university's theater department. "That's because the university head, though from the Taliban, loved theater. So we continued to produce plays, but for a restricted audience - the university boss and his friends. He allowed women to appear on stage, but controlled the content of the plays. So we could do a play, for instance, showing photographers harassing people and making money [the Taliban considered photography "un-Islamic"], but we had to steer clear of romantic or religious themes." The current revival is taking place in a climate of creative freedom. Many plays at the national festival have themes that are daring in Afghanistan - star-crossed lovers, hypocritical mullahs, corrupt provincial governors, smugglers of ancient cultural artifacts, and drug lords. But Afghans have not forgotten how to laugh - several plays take digs at doctors, policemen, and busybodies. "The aim is to establish theater as a common cultural domain that not only provides entertainment but also reflects the country's problems," says Julia Afifi, an Afghan-German director who has returned to her homeland to produce plays, teach at Kabul University, and help establish a national theater research center. Infusion of Western influences She is also introducing Afghans to Western plays and modern theater techniques. Among her current productions are short adaptations in the Dari language of Chekov's "Three Sisters" and British playwright Sarah Kane's controversial "Blasted," a searing portrayal of violence. "Afghans tend to adopt a declamatory style of acting, so I try to help actors liberate their emotions and bodies," she says. "I even show them [Quentin] Tarantino's films ["Pulp Fiction," "Kill Bill"] to demonstrate how violence can flow from normal, relaxed situations." For advocates, theater is a medium that can help Afghans not only to

emerge from a dark period, but also to examine and understand it. As

Naseeba put it, "Theater can help us find better ways to exist

in the future."

|

|