|

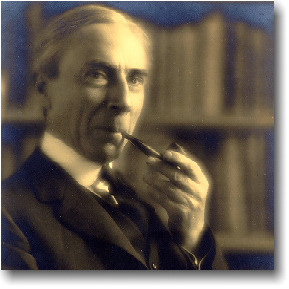

British philosopher, mathematician and social critic, one of the most widely read philosophers of this

century. Bertrand Russell was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1950. In his memoirs he

mentions that he formed in 1895 a plan to "write one series of books on the philosophy of the sciences

from pure mathematics to physiology, and another series of books on social questions. I hoped that the

two series might ultimately meet in a synthesis at once scientific and practical."

"The belief that fashion alone should dominate opinion has great advantages. It makes thought

unnecessary and puts the highest intelligence within the reach of everyone. It is not difficult to learn

the correct use of such words as 'complex,' 'sadism,' 'Oedipus,' 'bourgeois,' 'deviation,' 'left'; and

nothing more is needed to make a brilliant writer or talker." (from 'On Being Modern-Minded' in

Unpopular Essays, 1950)

Bertrand Russel was born in Trelleck, Gwent, as the second son of Viscount

Amberley. His mother,

Katherine, was the daughter of Baron Stanley of

Aderley. She died of diphtheria in 1874 and her

husband a twenty months later. At the age of three Russell was an orphan. He was brought up by his

grandfather, Lord John Russell, who had been prime minister twice, and Lady John.

Inspired by Euclid's Geometry, Russell displayed a keen aptitude for pure mathematics and developed

an interest in philosophy. At Trinity College, Cambridge, his brilliance was soon recognized, and

brought him a membership of the 'Apostles', a forerunner of the Bloomsbury Set.

After graduating from Cambridge in 1894, Russell worked briefly at the British Embassy in Paris as

honorary attachˇ. Next year he became a fellow of Trinity College. Against his family's wishes, Russell

married an American Quaker, Alys Persall Smith, and went off with his wife to Berlin, where he studied

economics and gathered data for the first of his ninety-odd books, GERMAN SOCIAL

DEMOCRACY (1896). A year later came out Russell's fellowship dissertation, ESSAY ON THE

FOUNDATIONS ON GEOMETRY (1897). "It was towards the end of 1898 that Moore and I rebelled

against both Kant and Hegel. Moore led the way, but I followed closely in his footsteps," Russell wrote in My

Philosophical Development (1959).

THE PRINCIPLES OF MATHEMATICS (1903) was Russell's first major work. It proposed that the

foundations of mathematics could be deduced from a few logical ideas. In it Russell arrived at the view

of Gottlob Frege (1848-1925), that mathematics is a continuation of logic and that its subject-matter is

a system of Platonic essences that exist in the realm outside both mind and matter. PRINCIPIA

MATHEMATICA (1910-13) was written in collaboration with the philosopher and mathematician

Alfred North Whitehead. According to Russell and Whitehead, philosophy should limit itself to simple,

objective accounts of phenomena. Empirical knowledge was the only path to truth and all other

knowledge was subjective and misleading. - However, later Russell became sceptical of the empirical

method as the sole means for ascertaining the truth, and admitted that much of philosophy does depend

on unprovable a priori assumptions about the universe. He, however, maintained otherwise than

Wittgenstein, that philosophy could and should deliver substantial results: theories about what exists,

what can be known, how we come to know it.

After Principia Russell never again worked intensively in mathematics. Russell's interpretation of

numbers as classes of classes was gave him much trouble: if we have a class that is not a member of

itself - is it a member of itself? If yes, then no, if no, then yes. After discussions with Wittgenstein Russell

accepted the view that mathematical statements are tautologies, no truths about a realm of

logico-mathematical entities.

Russell's concise and original introductory book, THE PROBLEMS OF PHILOSOPHY, appeared in

1912. He continued with works on epistemology, MYSTICISM AND LOGIC (1918) and

ANALYSIS AND MIND (1921). In his paper of 1905, 'On denoting', Russell showed how a logical

form could differ from obvious forms of common language. The work was the foundation of much

twentieth-century philosophizing about language. The essential point of his theory, Russell later wrote,

"was that although 'the golden mountain' may be grammatically the subject of a significant proposition, such a

proposition when rightly analysed no longer has such a subject. The proposition 'the golden mountain does not

exist' becomes 'the propositional function "x is golden and a mountain" is false for all values of x'." (from My

Philosophical Development)

In 1907 Russell stood unsuccessfully for parliament as a candidate for the Women's Suffragate Society,

and next year he became a Fellow of the Royal Society. Believing that inherited wealth was immoral,

Russell gave most of his money away to his university. His marriage ended when he began a lengthy

affair with the literary hostess Lady Ottoline Morrell, who had been a close friend of the Swedish writer

and physician Axel Munthe (1857-1949). Other liaisons followed, among others with

T.S. Eliot's wife

Vivien Haigh-Wood. Later Russell wrote about his sexual morality and agnosticism in MARRIAGE

AND MORALS (1929). Russell stated that human beings are not naturally monogamous, outraging

many with his views. In 1927 Russell wrote in WHY I AM NOT A CHRISTIAN that all organized

religions are the residue of the barbaric past, dwindled to hypocritical superstitions that have no basis in

reality.

At the outbreak of World War I, Russell was outspoken pacifist, which lost him his fellowship in 1916.

Two years later he served six months in prison, convicted of libelling an ally - the American army - in a

Tribune article. While in Brixton Gaol, he worked on INTRODUCTION TO MATHEMATICAL

PHILOSOPHY (1919). World War I darkened Russell's view of human nature. "I learned an

understanding of instinctive processes which I had not possessed before." Also Ludwig Wittgenstein's

criticism of Russell's work on the theory of knowledge disturbed his philosophical self-confidence.

Russell visited Russia in 1920 with a Labour Party delegation and met Vladimir Lenin and Leon

Trotsky, but returned deeply disillusioned and published his sharp critic THE PRACTICE AND

THEORY OF BOLSHEVISM (1920).

"The stuff of which the world of our experience is composed is, in my belief, neither mind nor

matter, but something more primitive than either. Both mind ands matter seem to be composite, and

the stuff of which they are compounded lies in a sense between the two, in a sense above them both,

like a common ancestor." (from The Analysis of Mind, 1921)

In 1922 Russell celebrated his 50th birthday, believing that "brain becomes rigid at 50." He was famous

and controversial figure - "'Bertie is a fervid egoist," Virginia Wollf wrote in her diary about his friend,

but Russell saw himself as "a nonsupernatural Faust." From about 1927 to 1938 Russell lived by

lecturing and writing on a huge range of popular subjects. He pursued his philosophical work in THE

ANALYSIS OF MIND (1921) and THE ANALYSIS OF MATTER (1927). Between the years

1920 and 1921 he was professor at Peking and in 1927 he started with his former student and second

wife Dora Black a progressive school at Beacon Hill, on the Sussex Downs. In ON EDUCATION

(1926) Russell called for an education that would liberate the child from unthinking obedience to

parental and religious authority. The experiment at Beacon Hill lasted for five years and gave material to

the book EDUCATION AND SOCIAL ORDER (1932).

In 1936 Russell married Patricia Spence, who had been his research assistant on his political history

FREEDOM AND ORGANIZATION (1934). In 1938 he moved to the United States, returning to

academic philosophical work. He was a visiting professor at the University of California at Los Angeles

and later at City College, New York, where he was debarred from teaching because of libertarian

opinions about sexual morals, education, and war. An appointment from the Barnes Foundation near

Philadelphia gave Russell an opportunity to write one of his most popular works, HISTORY OF

WESTERN PHILOSOPHY (1945). Its success permanently ended his financial difficulties and earned

him the Nobel Prize. In 1944 Russell returned to Cambridge as a Fellow of his old college, Trinity.

During WW II Russell abandoned his pacifism, but in the final decades of his life Russell became the

leading figure in the antinuclear weapons movement. From 1950 to his death Russell was extremely

active in political campaigning. He established Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation in 1964, supported

the Jews in Russia and the Arabs in Palestine and condemned the Vietnam War. In his family life Russell

had his own tragedies: his son John and his granddaughters Sarah and Lucy suffered from

schizophrenia. Russell turned over the care of John to his mother Dora. Lucy immolated herself five

years after Russell's death.

Retaining his ability to cause debate, Russell was imprisoned in 1961 with his fourth and final wife Edith

Finch for taking part in a demonstration in Whitehall. The sentence was reduced on medical grounds to

seven days in Brixton Prison. His last years Russell spent in North Wales. His later works include

HUMAN KNOWLEDGE: ITS SCOPE AND LIMITS (1948), two collections of sardonic fables,

SATAN IN THE SUBURB (1953) and NIGHTMARES OF EMINENT PERSONS (1954), and

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF BERTRAND RUSSELL (1967-69, 3 vols.), in which he stated:

"Three passions, simple but overwhelmingly strong, have governed my life: the longing for love, the

search for knowledge and unbearable pity for the suffering of mankind." Russell died of influenza on

February 2, 1970. When asked what he would say to God if he found himself before Him, Russell

answered: 'I should reproach him for not giving us enough evidence.'

Though Russell was a pioneer of logical positivism, which was further developed by such philosophers

from 'Vienna circle' as Ludwig Wittgenstein and Rudolf

Carnap, he never identified himself fully with the

group. In Human Knowledge: Its Scope and Limits Russell argued that while the data of sense are

mental, they are caused by physical events. The world is a wast collection of facts and events, but

beyond the laws of their occurrence science cannot go, it only gives us knowledge of the world.

|