|

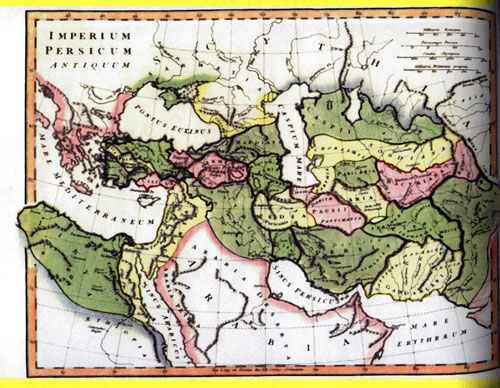

An early-nineteenth century map of the Persian Empire at

the time of Darius the Great, the third of the Achaemenian

King of Kings (522-486 B.C.) This map also shows the

twenty-two satrapie of the empire, each of which contained

a royal garden.

The Achaemenian spear established Persia's empire, an

empire that covered nearly two million square miles and absorbed nations

from Libya to India and from Greece to Ethiopia. The Achaemenian

government united the disparate peoples under a single rule, leaving them their cultures and their gods,

tying them together through far-reaching

chains of communication and sophisticated administration. The

Achaemenian genius, it seems, was for synthesis, in governing as in the

arts of civilization.

Thus the imperial culture that Cyrus and his descendants

created was a rich tapestry of many colors: Entirely new, it was woven

from threads as old as civilization itself. Achaemenian palaces

derived their style from those of subject peoples. Assyrians, Egyptians,

Babylonians, and Greeks, among others, built those soaring royal halls,

and all the peoples of the empire brought as tribute the objects that

adorned the buildings and their great gardens.

For these were garden palaces, with vast colonnades open

to the walled green spaces that surrounded them, and throne rooms

overlooking reflecting pools and groves of trees. They were

paradises in an austere wilderness; in fact, paradise derives from the Old

Persian pairi-daeza, "a walled space." The Greeks adapted

the word as paradeisos to describe the gardens of the Persian

Empire, and Greek translations of the Bible used this word as the term for

the Garden of Eden and for heaven. Modern Persian uses the arabized

version ferdows. As the word implies, the gardens of the Persian

kings embodied the images of sacred myth. To ancient man, the entire

natural world was charged with meaning: The gods were everywhere and

immanent. As might be expected in a region where all

of human existence depended upon agriculture, particular

power resided in water and trees, and the Mesopotamian

idea of an everlasting, ever-fruitful paradise was already

thousands of years old by Achaemenian times.

Fragments of the earliest known writing - that of

Mesopotamian Sumer of 2800 B.C. - include a poem

describing the creation of such a paradise, ordered by the

water god ad provided by the god of the sun. The

Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh, only slightly less ancient,

presents an immortal garden, centered on a sacred tree

that stand beside a holy fountain. The concept was

universal in Semitic myth.

The earliest historical records about

the Achaemenian "paradise" are those of the Greek author

Xenophon (ca 431-355 B.C.), a disciple of Socrates. In 401 B.C. he

describes the passion of Darius I for gardens: "....in all the

districts he resides in and visits, he takes care that there are

'paradises,' as they call them, full of all the good and beautiful things

that the soil will produce......." And in his Anabasis, he

expresses admiration for the way in which Cyrus the Younger (424-401

B.C.), the son of Darius and satrap of Lydia, looked after his large

garden at Sardis, which he had designed himself and in which he had

planted some of the trees with his own hands. As for the Persian'

love for shade trees, Herodotus describes how Xerxes, during his long

campaign against the Greeks in 480 B.C., stopped on the royal route and

saw a plane tree, the sacred tree of the Iranian plateau, which was so

majestic and beautiful that he decorated it with golden ornaments and appointed

a lifetime guard to watch over it!

As

the empire grew ever richer from the tributes of its

provinces-the famous satrapies - such paradises

proliferated. The Achaemenians were builders on a

grand scale. Cyrus began the restoration of the old

Elamite capital at Susa, Darius and Artaxerxes expanded it

to a city of palaces and courtyards covering more than

seven acres, all organized around a central garden.

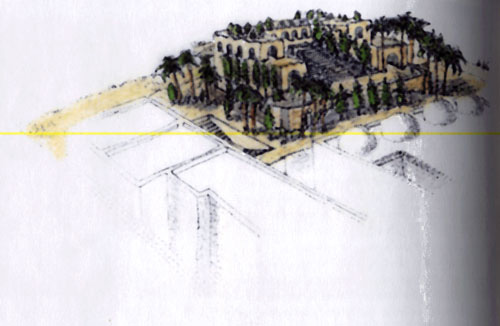

Susa was a winter administrative capital. To escape

the summer heat on the plain, the court moved with the

season to Ecbatana, the ancestral capital of the Medes six

thousand feet high in the Zagros, where the modern city of

Hamadan now lies. Inside the ring of seven walls set

to guard the city, they planted terraced gardens of great

magnificence. And the kings ordered paradises, with

trees in orderly rows and aromatic plants, created at the

satrapal palaces as well, so that the idea and the plants

spread throughout the ancient world. Thus Darius I

commending the garden of the satrap Gadatas in Asia

Minor: " It is evident that you devote your

attention to cultivating the land that belongs to me,

since you transplant into Lower Asia trees that grow on

the other side of the Euphrates; I laud your diligence in

this matter, and for it you shall enjoy great favor from

the House of the King." In fact, the import and

export of plants was a deliberate policy of empire.

The Achaemenians, according to the archaeologist Roman

Chirshman, introduced pistachios to Aleppo, sesame to

Egypt, and rice to Mesopotamia. Of

all the palaces that at Perseoplis, begun by Darius,

expanded by Xerxes and Artaxerxes I, pillaged and burned

in 330 B.C. during Alexander of Macedon's conquest,

remains the emblem of Achamenian glory. Yet it is

the one where paradise is difficult to imagine:

Although the architecture incorporates such plant forms as

the lotus, the rosette, the palm, and the fir tree, these

are lost on the impregnable platform fifty feet high, with

its reversing staircases wide enough for eight men to walk

abreast, its giant doorways, its fallen columns. The

plant become insignificant beside the endless processions

of subject peoples bearing gifts, the winged Assyrian

bulls that guard the gatehouse, the enormous mythological

animals and griffins that served as capitals for the

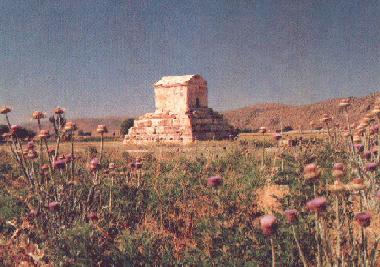

columns. To

recall the Achaemenian garden, it is better to return to

the tomb of Cyrus, the first and greatest of the Kings of

Kings, at Pasargadae. It is a lofty building, the

peak of its gabled roof rising forty feet above the

treeless, plowed fields around. Its monumental

simplicity has moved the hearts of generations. When

in 330 B.C. Alexander the great paused to salute it, he

found it set in a garden. According to Alexander's

biographer, the first-century Greek historian Arrian,

"The tomb of this Cyrus was in the territory of the

Pasargadae, in the royal park; round it had been planted a

grove of all sorts of trees; the grove was irrigated, and

deep grass had grown in the meadow...." The

tomb was a place of pilgrimage for Cyrus's successors, for

Alexander, and for other soldiers paying homage to

greatness. Some of them left their names carved on

the walls. In later centuries, as Cyrus was

forgotten, the tomb was named "The Shrine of

Solomon's Mother." A mehrb "altar"

facing toward Mecca was carved inside the building.

Beside it, village women praying for fertility hung bits

of votive cloth.

|