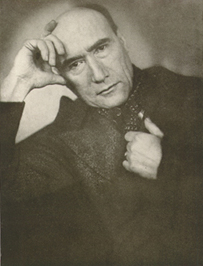

| Maurois was a French biographer, essayist, and critic.

In the following excerpt from his 1965 memoir of Gide, he discusses the

moral doctrine of Les nourritures terrestres (Fruits of the Earth - Rozaneh)

.

Like Thus Spake Zarathustra, Les Nourritures Terrestres is a gospel

in the root sense of the word--glad tidings. Tidings about the meaning

of life addressed to a dearly loved disciple whom Gide calls Nathanael.

The book is composed of Bible verses, hymns, recits, songs, rounds,

held together on the one hand by the presence of Nathanael and on the

other by the doctrine Gide seems to be teaching him. I say seems because

we shall shortly see that Gide would accept neither the idea of teaching

nor that of doctrine.

Besides Nathanael and the author, there is a third character in Les

Nourritures, one who reappears in L'Immoraliste and who is in Gide's

life what Merck was in Goethe's or Mephistopheles in Faust's. This character,

whom Gide calls Menalque, has sometimes been identified with Oscar Wilde,

but Gide told me it wasn't Wilde at all. Menalque is, indeed, no one

unless perhaps one aspect of Gide himself, one of the interlocutors

in the dialogue of Gide with Gide that comprises his spiritual life.

The core of the book was a recit by Menalque, one not far different

from a recit Gide might have given after his African rebirth....This

recit contains the essence of the "tidings" of Les Nourritures.

First a negative doctrine: flee families, rules, stability. Gide himself

suffered so much from "snug homes" that he harped on its dangers

all his life.

Then a positive doctrine: one must seek adventure, excess, fervor; one

should loathe the lukewarm, security, all tempered feelings. "Not

affection, Nathanael: love ..." Meaning not a shallow feeling based

on nothing perhaps but tastes in common, but a feeling into which one

throws oneself wholly and forgets oneself. Love is dangerous, but that

is yet another reason for loving, even if it means risking one's happiness,

especially if it means losing one's happiness. For happiness makes man

less. "Descend to the bottom of the pit if you want to see the

stars." Gide insists on this idea that there is no salvation in

contented satisfaction with oneself, an idea he shares with both a number

of great Christians and with Blake: "Unhappiness exaults, happiness

slackens." Gide ends a letter to an amie with this curious formula:

"Adieu, dear friend, may God ration your happiness!"

It would be a mistake to view the doctrine of Les Nourritures Terrestres

as the product of a sensualist's egoism. On the contrary, it is a doctrine

in which the Self (which is essentially continuity, memory of and submission

to the past) fades out and disappears in order that the individual may

lose himself, dissolve himself into each perfect moment. The Gide of

Les Nourritures Terrestres does not renounce the search for the God

Andre Walter was seeking [in Les Cahiers d'Andre Walter], but he seeks

him everywhere, even in Hell: "May my book teach you to take more

interest in yourself than in it, and more in everything else than in

yourself!"

There are many objections that might be made to this doctrine. First

one might object that this immoralist is at bottom a moralist--that

he does teach even though he denies it, that he preaches even though

he hates preachers, that he is puritanical in his anti-puritanism, and

finally, that the refusal to participate in human society ("snug

homes ... Families, I hate you!") is actually another form of confinement--to

the outside.

Gide is too intelligent not to have anticipated this kind of objection.

He raises it himself in Les Faux-Monnayeurs. In describing Vincent's

development, he writes: "For he's a moral creature ... and the

Devil will get the best of him only by providing him with reasons for

self-approval. Theory of the totality of the moment, of gratuitous joy

... On the basis of which the devil wins the day." A subtle analysis

of his own case: the beast has found a new way of playing the angel

who plays the beast. If the Immoralist weren't a moral being, he would

have no need to revolt.

One might further object that this is the doctrine of a convalescent,

not a healthy man.... But again Gide has taken care to raise this point

himself in the very intriguing preface he later added to the book, and

to point out further that at the time when he, the artist, wrote Les

Nourritures Terrestres, he had already, as a man, rejected its message,

for he had just got married and, for a time at least, settled down.

Moreover, he followed Les Nourritures with Saul, a play which can only

be interpreted as a condemnation of seekers after the moment and sensation.

Thus, Gide's wavering course between the angelic pole and the diabolic

pole is not all broken by Les Nourritures Terrestres.

How should it be when at the end of the book the master himself advises

his disciple to leave him....

But why doesn't Gide require of himself the same rejection he so strongly

urges on his disciple? And if he has a horror of any and all doctrine,

why isn't he horrified by his own? He is much too much Gide to be Gidean.

He always protested against people's habit of reducing him to a rulebook

when he had attempted, contrarily, to create a rulebook for escape.

This is Gide's supreme and perilous leap, the leap that makes him impossible

to pin down. What others might find to condemn in him, this Proteus

condemns in himself.

This brings up an extremely interesting question. Why is this subtle,

Protean doctrine which constantly denies itself, why after thirty years

is this powerful and dangerous book, still such a source of joy and

enthusiasm to so many young men and women? Read Jacques Riviere's letters

to Alain-Fournier; read in Martin du Gard's La Belle Saison the account

of the hero's discovery of Les Nourritures Terrestres; listen, finally,

to some of the young people about you. Many of them intensely admire

this book--with an admiration quite beyond the literary. Here is why.

With the discovery of the harshness of life, the magical and sheltered

days of childhood are followed, with nearly every adolescent, by a period

of rebellion. This is the first adolescent "stage." The second

stage is the discovery--despite disillusionments and difficulties--of

the beauty of life. This discovery ordinarily occurs between eighteen

and twenty. It produces most of our young lyric poets.

The special thing about Gide's character, its originality and its force,

is that, having been retarded in natural development by reason of the

constraints of his upbringing, he went through this second stage when

his mind was already relatively mature, the result being that this retardation

enabled him to express the discoveries common to all young people in

more perfect form. In other words, young people are beholden to a retarded

and unregenerate adolescent for having so well expressed what they feel.

Thus, the necessity, the universality, and the likelihood of endurance

of a book like Les Nourritures Terrestres. A disciple (as in Wilde's

fine story) is someone who seeks himself in the eyes of the master.

The young look for and find themselves in Gide.

Readers will find this same lesson in immoralism in Le Promethee Mal

Enchaine.... Gide calls this book a sotie, a Middle Ages term used to

denote an allegorical satire in dialogue form. Prometheus thinks he

is chained to the peaks of the Caucasus (just as Gide once was by so

many shackles, barriers, battlements, and other scruples). Then he discovers

that all that's needed is to want to be free, and he goes off with his

eagle to Paris where in the hall of the New Moons he gives a lecture

explaining that each of us is devoured by his eagle--vice or virtue,

duty or passion. One must feed this eagle on love. "Gentlemen,

one must love his eagle, love him so he'll become beautiful." The

writer's eagle is his work, and he should sacrifice himself to it.

|